When Your Child Has Infantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

The pylorus is the valve between the end of the stomach and the start of the small intestine. The pylorus opens to let food out of the stomach and into the small intestine. Then it closes. If the muscle around the pylorus thickens, the pylorus can’t open all the way. In children, this problem is called infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Food can’t leave the stomach to be digested. This means the body can’t absorb nutrients, leading to malnutrition. And it can’t absorb fluids, leading to fluid loss (dehydration). Infantile pyloric stenosis can happen when a baby is 1 to 2 months old. Experts are not sure what causes it. But it seems to run in families.

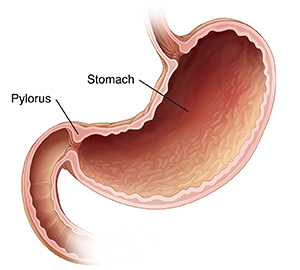

|

| The pylorus opens to let food out of the stomach into the small intestine. |

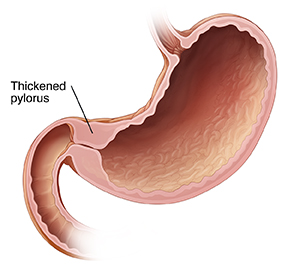

|

| With pyloric stenosis, thickened muscle around the pylorus prevents food from leaving the stomach. |

What are the symptoms of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis?

A child with pyloric stenosis may have:

-

Vomiting, often forceful (projectile vomiting)

-

Hunger right after vomiting

-

Loss of weight or poor growth despite good appetite

-

Signs of dehydration such as less urine, very dark urine, dry mouth, and no tears when crying

-

A lot of stomach movements after feeding

How is infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis diagnosed?

During a physical exam, the healthcare provider may be able to feel a lump of thickened muscle through the belly (abdominal) wall. Your child may need tests such as:

-

Abdominal ultrasound. Sound waves are used to create an image of the inside of the abdomen and the pylorus.

-

Upper GI (gastrointestinal) X-ray. An X-ray image is taken of the top of the small intestine, which shows the pylorus. This may be done if the lump can't be felt or the ultrasound isn't clear.

How is infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis treated?

Pyloric stenosis is treated with surgery. The surgery may be done with several small incisions (laparoscopic surgery). Or it may be done with one larger incision (open surgery).

If your child is dehydrated, this must be treated before surgery can be done. Fluids are given through an IV (intravenous) line. These replace the fluids your child’s body has not been able to absorb. Blood tests may also be done to check for problems that dehydration may cause.

After dehydration is treated, surgery is scheduled. During surgery, the thickened muscle is cut. The stomach contents can then flow into the intestine. In most cases, your child can start eating again about 3 to 4 hours after surgery. Your child can go home about 24 hours after surgery.

What are the long-term concerns?

After treatment, most children don’t have long-term problems. In the short term, your child may still have some vomiting or reflux. Reflux is a small amount of liquid coming up from the stomach into the mouth. This is normal for a short time after surgery. It should go away as your child heals. Even after surgery, there is a small chance the muscle around the pylorus will thicken again.

When to call the healthcare provider after surgery

After surgery, call the healthcare provider if your child has any of these:

-

Vomiting that won’t stop or looks green

-

Crying that can’t be soothed, which can mean your child is in severe pain

-

Weight loss or no weight gain

-

No bowel movement within 2 to 3 days after surgery

-

Signs of dehydration such as less urine, very dark urine, dry mouth, and no tears when crying

-

Low energy

-

Fever of 100.4ºF ( 38.0°C) or higher, or as advised by the provider